8 Minutes From The Sun

A solo show by Stephanie Teng

Square Street Gallery, Hong Kong

22.12.2021- 06.06.2022

Two years a million miles

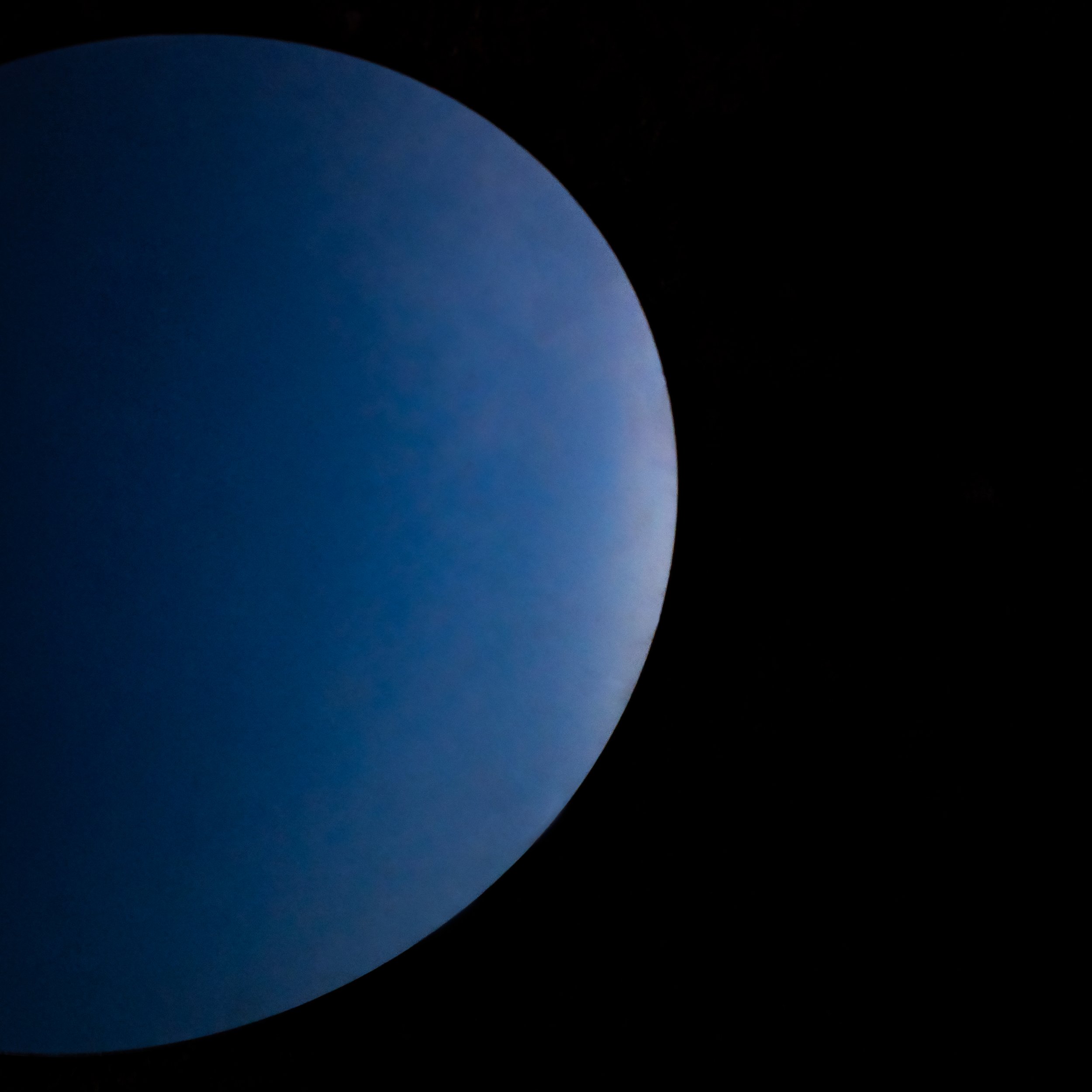

We have long known that to look up into the night sky is to look far into the past. Looking up at the star Sirius, we are seeing nine years into the past. Looking over at the star Antares, we are seeing 250 years into the past. Looking farther still at the Andromeda galaxy, we are seeing a million years into the past.Thus we see its surface not as it is now, the light of the sun takes 8.25 minutes to reach us.

The sunlight by which we see is ancient and so the great mystery of time is on display for us at every moment. 8 Minutes from the Sun is the new body of work by Hong Kong artist Stephanie Teng. Her multi-media installation, produced over two years, is composed of photographs, light, sound and objects.

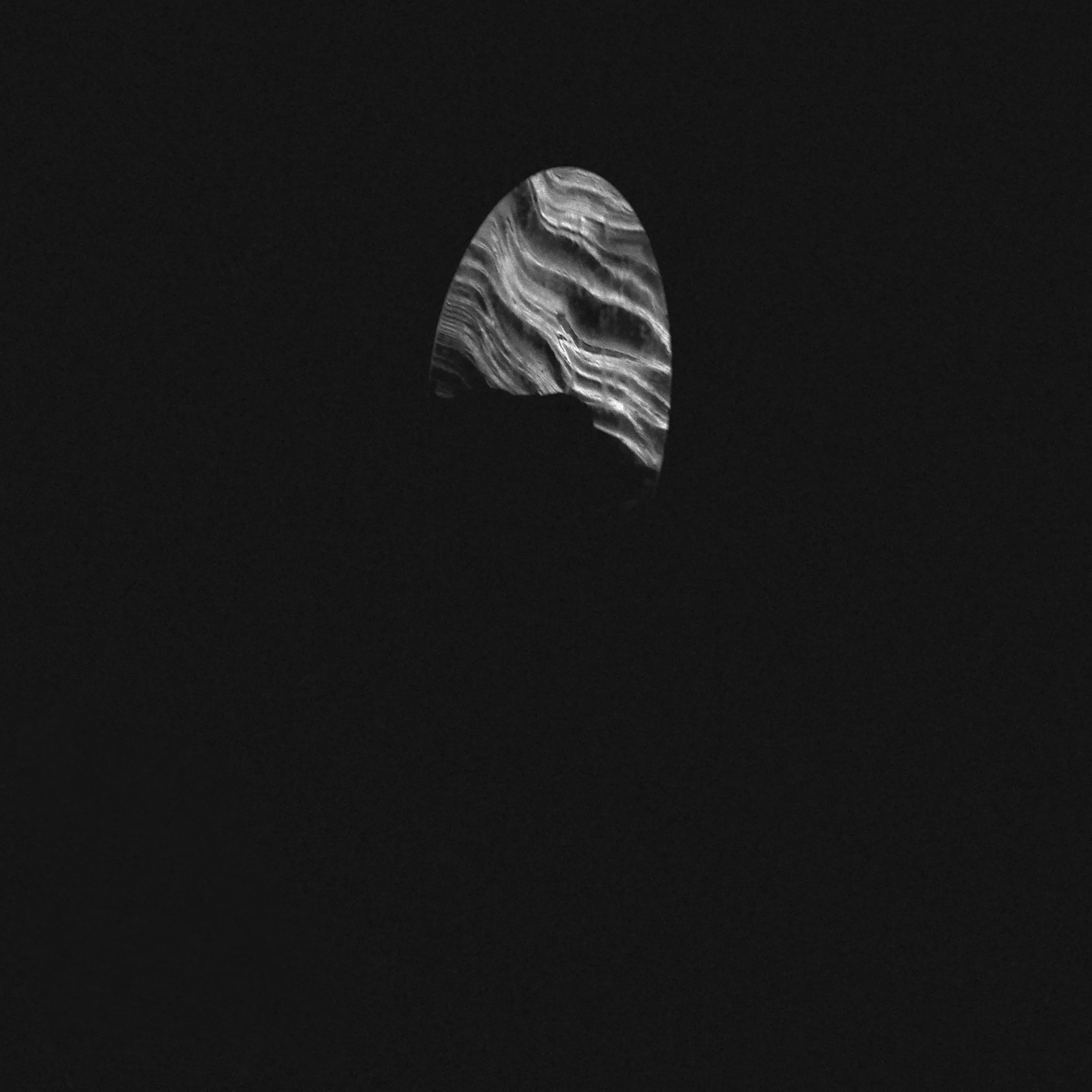

Minimal and geometric, the photographs of circular mirrors against textured backgrounds of stone and water reflect light back at the viewer. This abstraction of place, focusing on the minute details speaks to the intimacy found in memories of a place of frequent return. Part of the exhibition is the mirror used to create the images. Entombed within black pigment it no longer reflects outward but is transformed into something more: it becomes a focal point, a vessel that carries with it the story of the photographs.

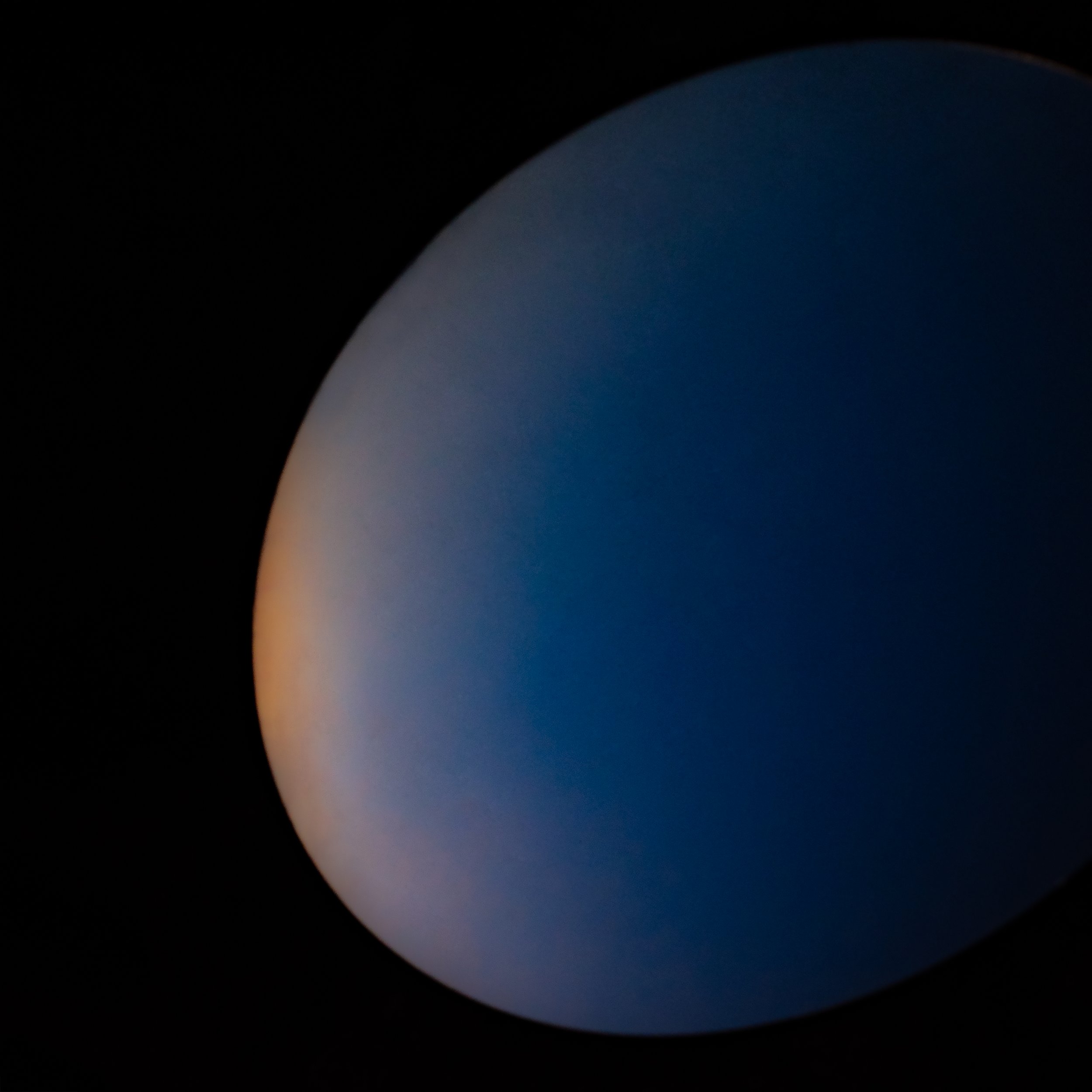

In the adjacent room, Teng has created an installation of light, sound and water. This work projects the sensory memory of place and time outward into the gallery space. The skylight reflects off an artificial pool of water and dances all around the room. Similar to a photograph, or to a shadow projected on the wall of a cave this attempt to represent the warm light of sunset reflecting off of the water onto the rocks signals the absence of the real thing but evoking a strong sensory response.

There is an alchemic resonance to the images, installation and object in the installation which break down the scene into base elements; stone, water, light and sound. Likewise, the titles of the individual photographs when combined form a poem:

I wish you would notice, the edges of our

erasure - at least for now.

We are falling in time: Nothing comes from

nothing; Nothing Feels like everything.

What Shall Not Remain;

Will Still Forever Exist.

This recombination of elements attempts to preserve memory but acknowledges that this alchemy is flawed. What remains is merely a reflection of lived experience, an echo of something no longer in existence like the light of a dead star.

8 Minutes from the Sun engages the natural world through the search for equilibrium between different states of being: stillness with motion and balance with imbalance. The gallery is bathed with the golden hour lighting, making the experience of moving between the images not only an exploration of light and space, but also a profound and awe-inspiring experience. The idea of unus mundus comes from an alchemical notion, popularised by Carl Gustav Jung, of an underlying unity in reality, from which emerges all the archetypes and which is at the core of the synchronicity. The system of the exhibition tends to then create simple but subtle forms of synchronicities for each spectator. Stephanie’s Teng photographs are maps drawn for journeys to inaccessible places. The maps combine naturescapes with mindscapes. In various ways earth and flesh reflect each other, combine in contrast with one another and illuminate each other to produce maps to places in ourselves we rarely see clearly. Seeing the photographs through the eyes of the soul opens all visual barriers and carries the mind through the birth canal of experience to the ocean of total awareness. Being in the moment, free of past associations, becomes the door to the unnamable. When one is part of the flow of the universe, what was a wave's reflection or a portion of a rock becomes a visual experience recorded in the awareness of the moment.

If the spiritual, even loosely defined, is a realm beyond the actual, then photography’s relation to it is bound to be complicated. Picturing the spiritual must either go through the actual, or somehow slip around it. In this sense, photography is, like us, straddling the cold facts of immediate existence and loftier ideals. Forty years ago, the critic Rosalind Krauss was writing about how, in the 1920s, Alfred Stieglitz began a large body of photographs of clouds, which he named Equivalents. He pointed his camera upward to frame and give form to portions of the sky, but aimed to transcend the literal. The label Equivalents was a way of asking the viewer to see his images as more than they were. No doubt we have all felt at least something numinous while contemplating clouds, or even photographs of clouds, so why couldn’t Stieglitz leave his photographs untitled, and leave us to respond for ourselves? Was he anxious that a photograph of clouds might be just that, and no more? Part of photography’s claim to high art was that it had access to realms beyond the immediate. Where mere photographers confined to reality, photographic artists could transcend it. Even so, actuality is always the portal to deeper thoughts and feelings because it is all we have to go on. An experience from daily life prompts a daydream, and the sheer mystery of human existence confronts us with how little we really know. It’s in the Celestographs August Strindberg made, in the 1890s, by leaving sensitised photographic plates on the ground overnight, facing upward toward the sky. He suggested that the mottled and colourful swirls were the heavens transposing themselves without need of a camera, through some cosmic will. They do look kind of astronomical and maybe that was his point. He also had a more mystical belief that “everything is created in analogies, the inferior with the superior.” Heavens and earth, base material and lofty aspiration.

Neither the Equivalents, the Celestographs nor the images from 8 Minutes from the Sun are purely photographic since they rely upon emphatic titles to guide our response. Nevertheless, we don’t require directives to enjoy such images in our own ways.

The meaning of art resides with us viewers.Yet particularly in Teng’s work, one is not exactly transported to another place. Rather, through her work one is ushered into a state of hyper awareness, of the pieces themselves and more to the point of one’s own consciousness.