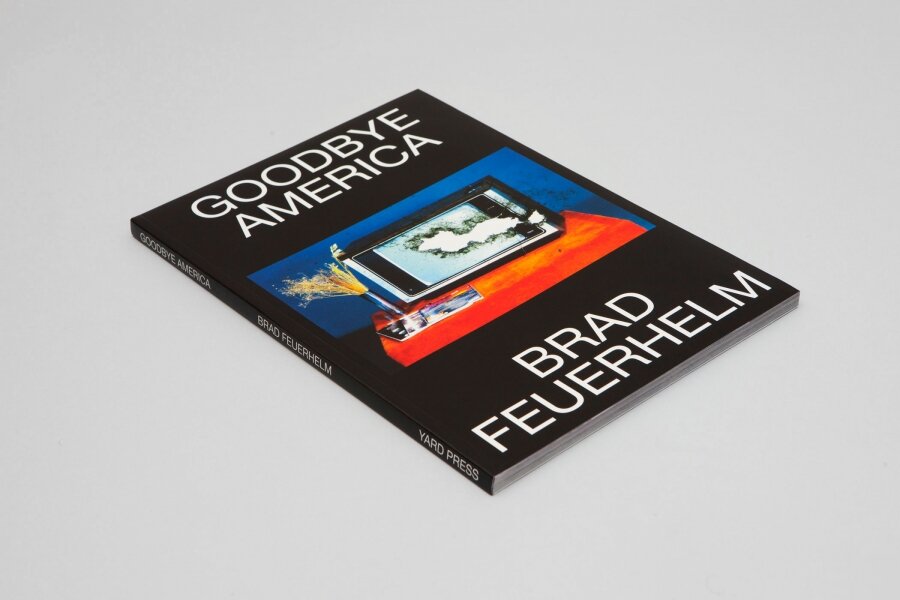

Brad Feuerhelm / Goodbye America

Photomonitor UK | February 2017

FMH: Could you tell us a little about your background as an artist and your work as the managing editor of American Suburb X? How does your curatorial practice relate to these?

BF: They are all fairly fluid endeavours. I also sell 19th and twentieth century vintage photography. I went to art school in Minneapolis where I studied bronze casting then photography alongside art history while working in a well-placed gallery. The curatorial practice actually takes the least amount of my time. That being said, I am opening a gallery with a friend in Athens this spring during Dokumenta, so it looks like it will return. Writing is something I do as a creative gesture or a response to something that interests me. It is not something I ever desired to do.

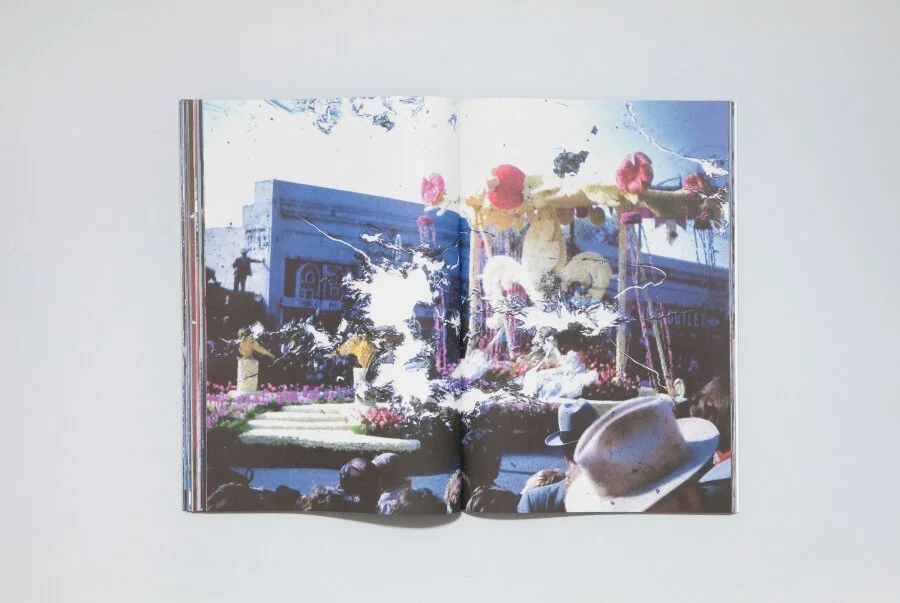

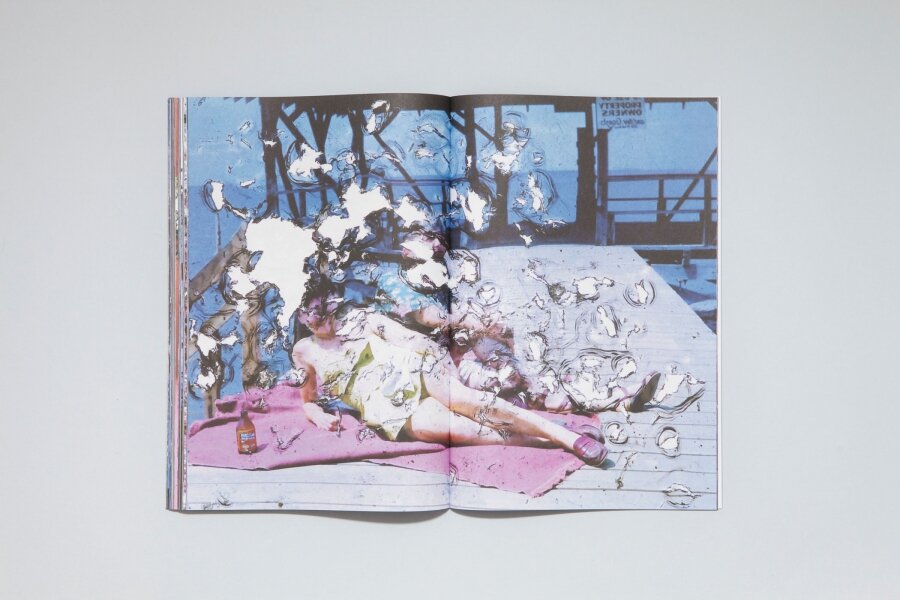

FMH: Your new volume, Goodbye America, drives us through a sequence of defaced images, a target shooting of iconic “American dream” photos. Could you tell us a little bit more how this project began?

BF: Well, most of my books, if one has seen them, are a direct reflection on my feelings towards America, the book Soft Touch being the only exception. I guess as an American abroad I feel a seething sense of anger towards the idea of America over the time I have been away, perhaps my eyes have just opened more to its hypocrisy. So this volume is in line with my work on America. It also works with my collecting habits and the re-purposing of material from my collection. I had spoken with the Yard Press guys off and on and they sprung a slightly different idea at me in the beginning, so I swung this one back to them.

FMH: Could you talk to us about Goodbye America and how these images were chosen, what attracted you to the this topic?

BF: The election certainly had much to do with it, but it started from my practice and working with images. They were not all American, as it were, when I started. They became edited into that later on. I have a substantial slide library/collection/archive so I picked images that I was also blasting with a blow torch at some point. I was looking to enable them through error or perhaps an enforced serendipity.

FMH: The images in the book are all smashed, scratched, distressed, destroyed. One of the earliest terms to describe destruction of images is ‘Damnatio Memoriae’ (Condemnation of memory) referring to the destruction of political idols and names in Ancient Rome as a severe punishment. Other forms of image destruction that come to mind are Iconoclasm, originally referring to the destruction of religious idols but later evolving to encompass destruction of established belief systems in general and vandalism, originally characterising the defacement of property in raids attributed to Germanic tribes but later justified by Gustave Courbet as a destruction of ‘monuments of war and power’ and seen as an artistic alteration or rebellion. There are of course other ways to look at this form of destructive mark making or gesture as well. In what mode of image defacement do you place your photographs?

BF: Fantastic question! I appreciate your digging into that! On the note of Courbet, who is one of my favourite painters, and this is me being a pedant, I should point out that his involvement of the destruction of the Vendome Column to which you must be referring is often cited as his act. His suggestion, in the tradition of Proudhon’s “Property is Theft” was to actually remove the column by disassembly to Napoleon’s tomb near Invalide. He was not actually the iconoclast himself, but he was made to pay for it several times over and forced himself into exile, dying one day before the first re-payment of the newly reconstructed column was due to be paid. In a sense, he is not an iconoclast at all. That is a popular misconception.

With my own work, what you are seeing, within your selection of categories is probably closest to something in between the condemnation of memory and iconoclasm, but can never truly be either. At the risk of further pomposity after my Courbet aside, I would suggest that the work is not a condemnation of memory as collective memory is something that is suggested as universal, more than relative and this act is personal. It is not political for others. I tend to keep my tribalism to my family and not a set structure of ideologues. On the iconoclastic tendency, since it is invariably personal and without a concretized representation of what “THE American Dream” constitutes, it somehow shirks the responsibility of vandalizing its image or the meaning broadcast by it.

FMH: In Goodbye America, it seems to me, the images are encountering the same destiny of a sort of ‘damnatio memoriae’. Why did you decide to intervene in that way on the images? How did you damage the images, and was it carefully controlled or more random?

BF: Much of my interest in photography is about error and failure. I have written a bit on Vilém Flusser and the apparatus and distribution of intent within the vaunted term “photographic language” and the ability for serendipity and the loss of representation to be an enabler over that of a detractor. And perhaps it is my previous experiences with sculpture, but I am interested in topics of the void, art and destruction and so forth. The physical images were originally slide images in original mounts made on 35mm film, so a very tiny surface. They were smashed sometimes with one blow of the back side of a European hammer. Sometimes I would choose to facilitate several blows. The image base, the uncorrupted or undestroyed slide usually dictated that simply by its composition. Portraits were generally assigned one strike. But, sometimes you miss, and breaking something perfectly, however unique, goes awry.

FMH: How did you get the images for this book? How big was the archive from which you chose these images? How do you select and edit when approaching this topic?

BF: As a collector, it [the archive] is always at hand and a large amount of my daily practice does indeed revolve around images I gather. It’s fairly fluid at maybe 5,000 images, but most of those are highly specific, so I added a few groups from ebay. We selected the works together. I see the book as a design and editing collaboration. I started with the base, the core images and gave it to Achille and Giandomenico at Yard and let them do their thing. I am not a designer. I actually loathe that bit except for when it comes to choosing a cover.

FMH: Archival material plays an important role in a number of curatorial works, research and exhibitions. Do you think you have a particular way of seeing the world that’s related to archival research, archival photographs?

BF: I would say I am more interested in looking at things from a more difficult perspective. There are many people who work with vernacular and archival material. It’s kind a limp crutch in some cases, but I would say between the tropes of violence, death, existential interest and perhaps a draw towards the perceived values of “the unseen”, my practice or productions border on the commonality of the violently moribund. I don’t see many other people diving into the “difficult to look at” material.

FMH: One of the essays in the book, the one by Anthony Farinelli illustrates a short history of the American imperialism linking it to early colonialism and eventually arriving to the ideological background that he proposes the source images are holding up. Do you see the text as essential to reading the photographs or do you see it as existing alongside or complementary?

BF: I see no text as essential to reading anything. That sentiment has nothing to do with Anthony. I did not spell things out for either of my collaborators on this, the title kind of carries relative weight there. That being said, I love love love both essays. They are written by friends and Americans living in London. At the time the book started its process, I had just left there myself. We have all known each other for years and share similar perspectives though I feel Anthony is way more balanced in his assessment not only of contemporary conditions, but his insight into what I left unspoken, of my character, etc are essential to my reading of the book and our continued friendships, same with Ryan.

FMH: I would like to know more about your methodology. How does your work usually evolve? What kind of strategies do you put in place in order to translate your research visually?

BF: I work all of the time. Working is a process. I think artists exist in different states when they create. Some artists tend to really research and work on one idea years before letting a pencil touch paper, a paintbrush canvas or a shutter a plane of photosensitive surface. That is great for them, but I work constantly. I fill sketchbooks, I write, I obnoxiously upload my instagram with very difficult material in hopes that people start their days right. I absorb, its kind of a state rather than a method. Everything is linked. The music I listen to, the youtube documentary playing in the background as I scan photographs, the books I review for American Suburb X and importantly, the images I collect. I am drawn to sensory experience.

FMH: The title of the photo book could easily be viewed by some as very relevant to the recent election results, was that deliberate?

BF: The entirety of the book is about the state of America during the election period in particular. It is a nod towards the idea of imperial decline and the paucity of America’s ability to genuinely hold the mirror up to itself.