Ioanna Sakellaraki / The Truth is in the Soil

Photomonitor UK| October 2020

Memory, family, loss, grieving – these universal ideas resonate differently through generations and cultures. Below, Francesca Marcaccio Hitzeman speaks with Ioanna Sakellaraki about her recent work investigating these truths and their exploration within the photographic medium. Her resultant series ‘The Truth is in the Soil’ is currently being shown in various venues in Europe, and we are grateful to share her insights with Photomonitor readers, below.

FMH: Could you tell us a little about your background as an artist and what attracted you to photography?

IS: Hello, I am Ioanna Sakellaraki, thank you so much for having me. I am a Greek artist based between Brussels and London and recent graduate from an MA Photography at The Royal College of Art. I would say that my photography started evolving already back in 2011 while I was completing my MA in European Urban and Cultural Studies. In that context, I carried out a series of research projects on urban planning, architecture and cultural development, paired with my background in journalism, and I gradually began to work on visual narratives around memory and territory, with a focus on architectural ruins and historical landscapes.

Since then, I have worked on a series of personal projects and assignments with a strong interest in the relationship between photography and global and social systems of power, both in historical and contemporary contexts. As my artistic practice slowly emerged, I have been interested in how photography as a medium is always characterized by a discontinuity in time and place, ‘’between the moment the image is recorded and the moment that the image is viewed or looked at’’ is what John Berger calls an ‘abyss’. This discontinuity and isolation of appearances in the photographic, the way the image affirms things in their disappearance and gives us the power to create absence through fiction, was what became a trigger for exploring the medium and its possibilities further, within my own narratives.

FMH: Inspired by the ancient Greek laments, and revolving around loss, memory and fiction, your latest project ‘The Truth is in the Soil’ dwells within traditional communities of the last female mourners inhabiting the Mani Peninsula in Greece. Would you tell us about what motivated this series?

IS: ‘The Truth is in the Soil’ started evolving four years ago, when the death of my father sparked a journey back home and the exploration of traditional Greek funerary rituals. Portraying my mother as a mourning figure within the social and religious context of my country, I began to slowly unravel a personal narrative of loss interweaving fabrications of grief in my family and culture. Endeavouring to further understand my roots, and after I received The Royal Photographic Society Postgraduate Bursary Award 2018, which did not only financially support this long-term photographic research, but also set a mental framework around this body of work, I expanded the scope of my research on the collective mourning and ritual laments of the last communities of professional mourners in the Mani peninsula of Greece.

While most know the Mani peninsula in Greece for its breathtaking cliffs and quaint coastal villages, it is also home to a tradition of ritual lament that dates back to ancient times. Considered an art, ‘’moirologia’’ (Fate Songs) can be traced to the choirs of the Greek tragedies and over the centuries, it became a profession exclusive to women. Today in the Mani peninsula live some of the last professional mourners of Greece. The aging of the villages in the region and the difficulties during the current economic woes besetting the country seem to be part of the reason for the disappearance of the dying art of professional mourning.

In the crossroads of performance and staged emotion, I look at how the work of mourning contextualises modern regimes of looking, reading, and feeling with regards to the subject of death in Greece today.

FMH: I can only assume ‘The Truth is in the Soil’ images must have been orbiting your imagination for some time before putting together the final project. Where and when did you first decide to make this body of work and to what extent has your relationship to it changed over time?

IS: My process of documenting the communities of mourners was substantial for the initial stages of this body of work. During my making process, it has been important for me to carry out the work on the field, finding the real women and documenting their reality in the remote villages of the region. However, making a work about grief requires a journey through memory and memory loss. As I continued to work on the project, the first figurative portraits of the mourners that I reconstructed in my studio, made me question how both the work of mourning and the photographic effect perform their work by arresting time and disordering memory.

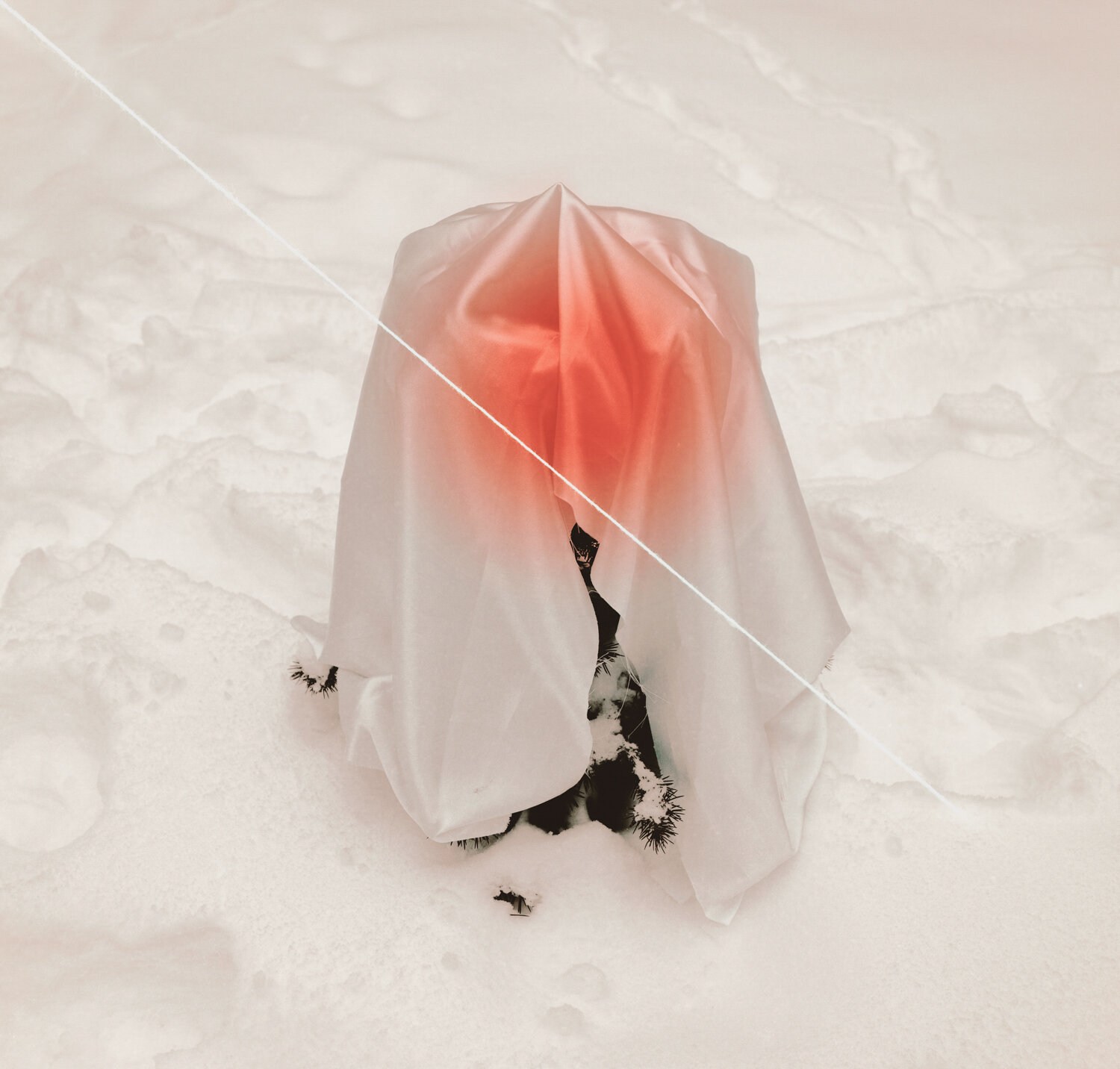

I gradually became interested in how space can be indissolubly perceived and represented in the process of reworking memory and negotiating the boundaries of grief in my work. The idea of the silhouette started influencing the sequence of portraits that followed. While constructing the final pieces, shot in medium format film, I experimented by post-editing my film negative and playing with inverted light and shade, relief and contour, exploring the inherent recognizability of each figure’s outline.

During my making process, I moved from the original figure to its concealed form where the distinction between the real and the imaginary led to a tangible experience of separation. Through my images, this separation became an encounter. The human figures of the female mourners turned into the landscapes themselves, functioning as passages between sheltering something from death and establishing with death a relation of freedom.

FMH: It seems to me that in the process of speaking about death as a passage through time and memory in the archive, you have created a language of mourning/narrative of grieving using elements of performance, sound and embroidering materials . Can you talk more about this?

IS: Expanding from how the image reanimates language, my practice has been revolving around the ways the mourning process enables a creative relation to the object. In a more recent part of this body of work, I have developed a series of artworks combining mixed media textiles and hand stitched embroidery on archival photography. During my making, I have used dye sublimation printing on woven fabrics, integrating free hand embroidery and mark making techniques on the final pieces. The work brings together my father’s photographic archives from 50 years ago and traditional hand embroidery stitching my mother has been practicing, during their time apart, throughout his journeys away as a sailor. The final artworks are a result of a collaboration and exchange between me and my mother as the images are posted between the cities we live and once delivered we both proceed in continuing from each other’s embroidery act. As a result, a language of thought that is spoken elliptically has emerged becoming a trace of a dialogue with oneself; an anonymity, an absence, a blank space.

FMH: I would like to know more about your methodology. How does your work usually evolve? What kind of strategies do you put in place in order to translate your research visually?

IS: ‘The Truth is in the Soil’ is about memory and memory loss, as the two subjects are wholly interconnected when venturing through an experience of grief. During my making process, I want to talk about what is lost; parts of memories that are reconstructed, just like how an image of a lost person appears in our minds after they are gone, just like how in the work of mourning, memory becomes what we remember forgetfully. I am always perplexed by how photography as a medium replaces absence with an imaginary presence and how images have the power to make things appear; things that are always deferred and absent others. In that sense, part of the narrative is re-imagined, deriving from the real but taking the viewer to an imaginary journey.

Greece is a constant inspiration and encounter in this work, but the way it is depicted is imagined. It is like the idea of the homeland being this place one knows outside of memory, a land of curiosity where death is an encounter through family, religion, mythology and the self. By consciously adding another layer of intervention to what has been documented as real, I aim at refiguring an absent language of thought around grief based on the rhythm of occurrence and deferral of the unspoken; death. In a way, these images work as vehicles for mourning perished ideals of vitality, prosperity and belonging, attempting to tell something further than their subjects by creating a space where death can exist.

FMH: Foucault defined counter-memory as the individual resistance against the official versions of the historical continuity: the important thing becomes who remembers, what is the context of memory and what does it oppose. Even the use of memory differs. Some past events are forgotten, others are immediately given importance and are considered worthy of memorizing, while some emerge on surface after a long period of oblivion. In your experience what are the reasons which lead to change in perception of memory and its reproduction?

IS: The discourse this question brings forth makes me want to share an extract from my writings (The Time of The Disaster: Everything I Remember Forgetfully, Royal College of Art, MA Photography Thesis, 2019) on memory and the photographic that better describes my critical reflection on this:

‘I see the image as it being there to affirm the disappearance of a moment, a moment of a human turned into an object for observation after he is gone; this unformed nothingness called death.

I abandon myself to what I see, and I feel so powerless and muted by it. I use my eyes to see but I see to also imagine. I imagine through the image. The image becomes the passageway between a liminal space of presence and absence, a resolution to the question of becoming through loss. I exile myself into the illusions of the image, looking for a world to resemble my dreaming. When does fiction become reality?

Zooming into the photograph something is there before me, resembling reality and death at the same time, it has existed but is never the same as when I first encountered it. It has disappeared but it is still alive. It is the same but different, alive but lost; a remain of the real but also an introduction to a dream. My dream becomes a nonplace, a nowhere that is situated here, and this is my sole connection to reality.

Like Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, sitting down to contemplate all those photographs found in a box after his mother’s death, none of them seemed to him really “right”, neither in terms of a photographic performance nor a living resurrection of the beloved face. As he says: “These photographs for some reason were part of an unknown history I had to learn while looking through them reminding myself of my nonexistence. A person I know but all different at the same time.”’

FMH: What are the key influences of your photographic experience? I’m thinking of life experiences, music you listen to, or literature which informs your world view?

IS: The abstract place that grief represents and its close relationship with language and space as modes of thought have led me to examining the relationship between fragment, rupture and separation. Drawing from Roger Caillois’s writings on camouflage and the need of deception in nature, I have been researching how space can be indissolubly perceived and represented in the process of reworking memory and negotiating the boundaries of grief. The series of figurative portraits derive from the mourners’ silhouettes as a result of my making process of cutting out, drawing together, marking, and dissembling the original figures. This dissembling of the figure, “the sketching or spacing out of a between that persistently destabilizes the work by refiguring its absent origin”, inspired by the concept of “rift” introduced by Heidegger, leads to them becoming figures of nothing; through my effort to find language in its own hiding, they conceal themselves into their endless disfiguring. Inspired by philosophical poetics and aesthetics and more specifically the work of Aristotle on vision and theory as well as the dispersions of vision in Heidegger’s Being and Time, I have been reflecting on how the poetisizing projection of truth that sets itself into work as figure provides an allegorical description of the experience of death while revealing the relation of language and world as open and ungrounded.

FMH: Do you have any current projects that you are working on that you would like to discuss?

IS: I have been recently working on the curation of the work shown during the Athens Photo Festival at the Benaki Museum in Greece which just opened and will stay on until the 15th of November as well as a solo exhibition of ‘The Truth is in the Soil at Galerie Erstererster in Berlin during the European Month of Photography, 7-13 October. Aside from that, I aim to be working on my practice-led PhD which I just started remotely and spending part of the autumn back in Greece realizing new work that I will be excited to share with you, hopefully soon. In the meantime, I will be completing an artist residency this autumn on a Greek island, also practicing further my embroidery skills.